In a world of overwhelming complexity, our brains rely on mental shortcuts—known as heuristics or “rules of thumb”—to navigate daily decisions without becoming paralyzed by analysis. These cognitive tools allow us to make quick judgments based on limited information, enabling efficiency in a world where we face countless choices.

First systematically studied by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the 1970s, heuristics help explain why human decision-making often deviates from purely rational models. While these mental shortcuts serve us well in many situations, they can also lead to systematic errors in judgment—what psychologists call cognitive biases.

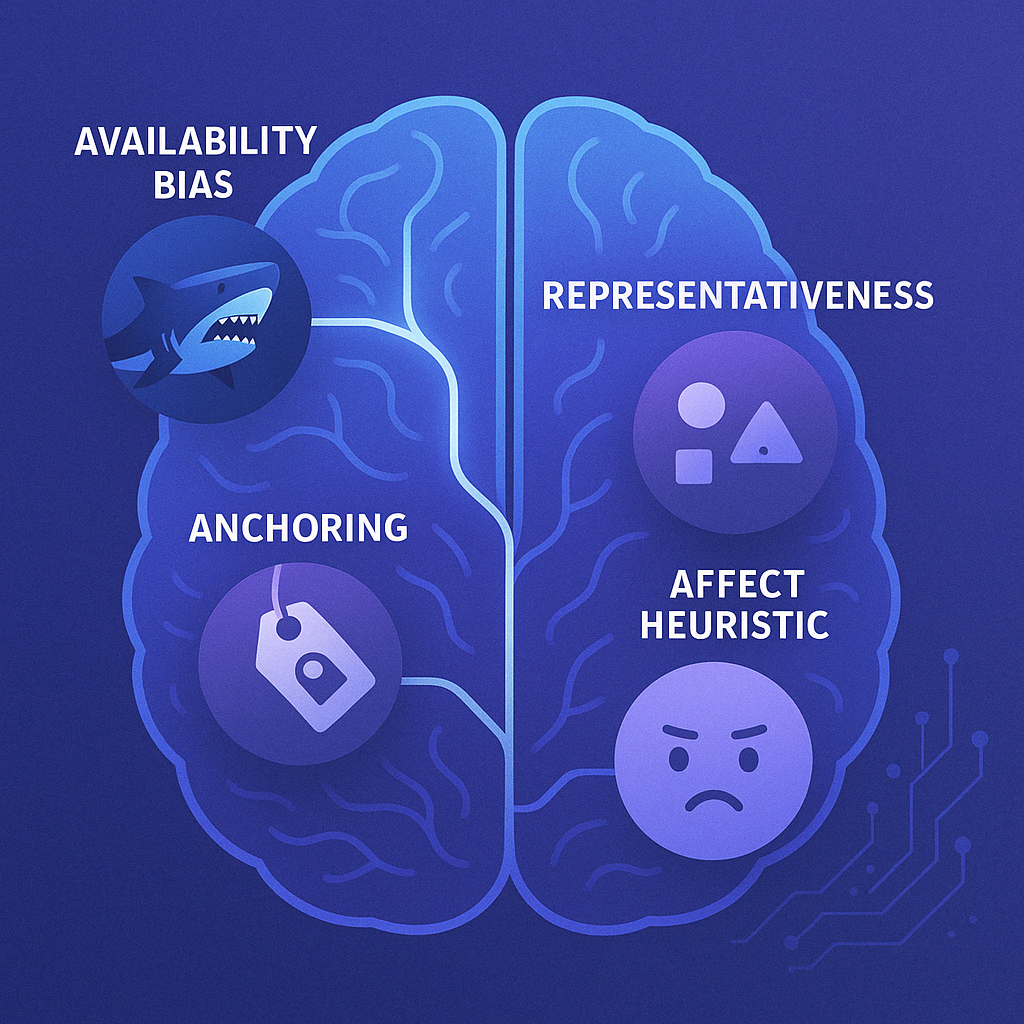

Common Types of Heuristics

The Availability Heuristic

The availability heuristic leads us to judge probability or frequency based on how easily examples come to mind. When events are vivid, recent, or emotionally charged, they become more “available” in memory and thus seem more common than they actually are.

Examples:

- After media coverage of shark attacks, beach attendance drops, despite the extremely low statistical risk

- Doctors sometimes overdiagnose conditions they’ve recently seen or studied

- Investors often give undue weight to recent market performance

The Representativeness Heuristic

This shortcut involves judging probability based on how similar something is to our mental prototype. If something matches our mental image of a category, we assume it belongs to that category.

Examples:

- Assuming someone wearing a lab coat is a doctor

- Believing that a company with a well-known brand must be financially stable

- Expecting that a sequence of coin flips should “look random” (avoiding patterns)

The Anchoring Heuristic

Anchoring causes us to rely too heavily on the first piece of information we encounter (the “anchor”) when making decisions.

Examples:

- The first price mentioned in negotiations strongly influences the final outcome

- Product pricing strategies that show the “original” higher price alongside the sale price

- Performance reviews influenced by first impressions

The Affect Heuristic

This mental shortcut involves making judgments based on emotional reactions rather than careful analysis.

Examples:

- Perceiving lower risk in activities we enjoy

- Making purchasing decisions based on brand sentiment

- Evaluating political candidates based on likability rather than policies

Why We Rely on Rules of Thumb

Heuristics aren’t flaws in human cognition—they’re adaptations that evolved for good reason:

- Cognitive efficiency: They conserve mental resources in a world of information overload

- Speed: They allow for rapid decisions when time is limited

- Simplification: They make complex problems manageable

- Pattern recognition: They help us identify meaningful patterns in noisy data

In ancestral environments with limited information, these shortcuts were often adaptive. However, in our information-rich modern world, these same mental processes can sometimes lead us astray.

Heuristics in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

Interestingly, artificial intelligence systems can develop their own versions of heuristics and biases. Machine learning algorithms, trained on human-generated data, often internalize and sometimes amplify the shortcuts present in their training data.

For example:

- Recommendation systems may overemphasize popular content (a form of availability bias)

- Language models may make predictions based on superficial patterns that resemble human representativeness heuristics

- Decision-making algorithms may give undue weight to certain features, similar to anchoring effects

Addressing Heuristic Biases Through Human-AI Collaboration

Human-in-the-loop approaches offer promising strategies for mitigating biases that arise from both human and AI heuristics:

1. Complementary Strengths

AI systems can be designed to flag potential heuristic biases in human decision-making, while human oversight can identify when AI systems are exhibiting their own algorithmic shortcuts. This complementary relationship creates a system of checks and balances.

2. Structured Decision Protocols

Combining human judgment with AI analysis through structured protocols can reduce the impact of heuristic biases. For example, having humans and AI independently evaluate the same data before comparing conclusions can highlight where availability or representativeness shortcuts might be influencing either party.

3. Diverse Review Mechanisms

Establishing diverse teams of human reviewers who evaluate AI outputs can help identify when systems are exhibiting heuristic-based biases. People with different backgrounds and expertise bring different mental shortcuts to the table, making it more likely that problematic patterns will be identified.

4. Counterfactual Thinking

Human-in-the-loop approaches can incorporate structured counterfactual analysis: “What if our assumptions are wrong?” Human reviewers can be trained to deliberately consider alternative scenarios that might not be as mentally available to either themselves or the AI system.

Conclusion

Rules of thumb are fundamental to how humans—and increasingly, AI systems—navigate a complex world. These heuristics offer efficiency and speed but come with predictable blind spots. By understanding the mental shortcuts that shape our judgments, we can develop strategies to leverage their strengths while guarding against their limitations.

The future of decision-making likely lies not in eliminating heuristics, but in creating systems where human intuition and artificial intelligence work together, each compensating for the other’s cognitive shortcuts. Through thoughtful human-AI collaboration, we can work toward decision processes that combine the pattern-recognition strengths of human intuition with the systematic analysis capabilities of computational systems—creating outcomes that neither could achieve alone.